Offset Printing Colour Management

Having a broad understanding of how colour is reproduced in the CMYK offset printing process is essential for anyone involved in print production. Since colour reproduction involves colour science, this article can get somewhat technical. However, I’ve tried to keep the technical details to a minimum. The intention here is to explain the practical processes a print business should carry out to achieve saleable colour that aligns closely with industry standards.

The Finger Pointing

Time and again, we encounter the following scenario: A critical job is printed, prepress produces the plates as usual, the press operator runs to their usual “ink weights” (or, shudder, to eye), the job is finished and delivered, only to be rejected by the client for not matching the expected colour.

Prepress blames the printer while the print room blames prepress.

Aside from the fact that the sales, approval, and quality control processes should prevent a finished job that doesn’t match the supplied target from being delivered to the customer, the reality of the technical cause of such issues lies jointly between prepress and press. Neither department can resolve the problem alone as both play a critical role in colour reproduction. The pressroom cannot significantly affect dot gain without compromising the solids, and prepress cannot influence the ink laydown or trapping on press.

The Reality

Setting aside artwork colour management done to the digital files prior to plate making, there are two main factors in colour reproduction on press:

- Solid ink colour on paper.

- Half-tone dot gain on paper and plate.

Ink Colour

Ink colour refers to the actual hue of a solid patch of ink on paper. It is a combination of the ink, the paper, and the thickness of the ink applied by the printing press, which is controlled by the press operator or the on press colour scanner. (Lighting is also a factor, but we will set it aside for now as we are focusing on the technical assesment of colour which includes a controlled light source, typically D50/D65, in the pressroom measuring device).

In the 1990s, in the pressroom, we would aim for an ink weight—a density—using a pressroom densitometer. The ink or press manufacturer, or sometimes a colleague, would provide guidance on the target weights to achieve “good” colour.

| Ink | Cyan | Magenta | Yellow | Black |

| Density | 1.35 | 1.40 | 0.95 | 1.65 |

However, this approach did not take into account the actual ink formulation or it’s interaction with the paper. The term “cyan” is meaningless until you know the exact cyan ink, the paper, the density, and the lighting used. Consequently, we moved long ago to a device-independent description of what the true colour of a solid patch of ink should be.

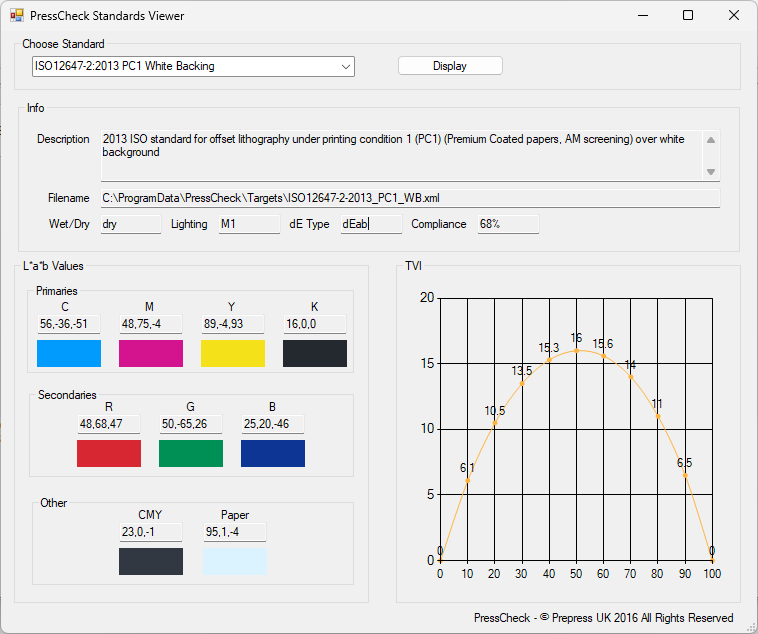

Assuming we are printing to an industry standard, for example, ISO 12647-2:2004 (often referred to as “FOGRA 39/47”) or ISO 12647-2:2013 (FOGRA 51/52), the standard defines a device-independent description of the colour of a 100% solid patch of the C, M, Y, or K ink as CEILAB values for each of Gloss, Matte, and Uncoated papers.

| Ink | Cyan | Magenta | Yellow | Black |

| L*,a*,b* | 56,-36,-51 | 48,75,-4 | 89,-4,93 | 16,0,0 |

The first step in achieving good colour is determining how much of your brand of ink needs to be applied to your chosen paper(s) so that when it dries, the solid ink falls within an acceptable tolerance of the specification defined in your target standard.

At Aldridge Solutions, we use a specially designed job to output a wide range of different ink film thicknesses on a single print. We note their colour and density when wet, then allow them to dry before measuring them with a spectrophotometer to check their CEILAB colour. Through this process, we work back to discover the wet ink weight that achieved the closest match to the target on the dry print. This target is then used by the printer, either with a hand-held densitometer or programmed into the on-press colour scanner.

The first part is complete—we now know how much ink to apply for good solids.

Halftone Dot Gain

In a perfect world, all printing presses would behave the same. We’d give them a linear plate, they would know how much ink to lay down, and the printed result would be consistent regardless of the location. However, this is not the reality.

Presses behave differently for a multitude of reasons, including:

- Environmental conditions like temperature and humidity

- Roller settings and quality

- Blankets and packing

- Ink characteristics

- Paper characteristics

- Fount characteristics

- Working order of the printing press (maintenance and wear)

It is always important to invest time and money in the basic maintenance of your press and the replacement of consumables to ensure predictable printing. Assuming this maintenance has taken place, the next step is to teach our prepress systems how our particular press, combined with our consumables, reproduces tints when laying down the correct amount of ink. This is the second step to achieving good colour on press and can only be adjusted through the use of calibration curves in the prepress workflow software.

At Aldridge Solutions, we start by plating a dedicated measuring and visual test form in prepress. We do this with linearised plate output and no other adjustments applied (with some processless plates, this can be challenging due to the lack of a visible dot. In such cases, we let the press calibration handle both plate and press adjustments, outputting the plate “as-is” with no calibration).

We run this test form on press using the same set of plates for each paper type the printer wants to characterise, at the ink weights or colours established in step one. Typically, we can use a single “coated” calibration for both gloss and matt paper and a second one for uncoated. However, specialist applications or the need to pass ISO checks regularly may require more curves for different paper types, necessitating additional test prints.

Once we have “good” sheets for ink weight for each paper type, we allow them to dry fully before measuring with a spectrophotometer and analysing the Tone Value Increase (TVI), often referred to as dot gain. This tells us, for example, that a 50% cyan tint on coated paper gains up to 72% on press, and so on for each colour and each tint step.

This process allows us to build an “Actual” press curve to inform the prepress workflow how our printing press behaves under these conditions. This curve is then combined with a “Target” press curve, indicating how we want the print to be reproduced. The workflow then calculates the necessary adjustments on the plate to move from the Actual to the Target, cutting or boosting the tints on the plate as required.

A press calibration is saved in the workflow for each paper type measured. Check plates are then produced using this new calibration, with one set for each of the target paper types. These are run on press to target solid colour, and the process of drying and measuring is repeated. Typically, the workflow will have used basic mathematics to transform the actual values to the target values, since the press does not respond in a linear fashion, a knowledgeable engineer will adjust the numbers the last few percent to achieve an closer match to the target.

For many printers, this process is sufficient. The plates produced by prepress with the new curves, when printed by the press minder to the correct ink weights, will require very little adjustment to achieve or closely match a digital proof run to the same target colour standard.

For those who need to pass ISO checks regularly or require a full compliance report, additional adjustments can be made to bring the TVI even closer to the target, to balance the three-colour C, M, Y greys, and to achieve the closest match on the secondary colours R, G, and B.

How Often

The inevitable question I am asked at the end of every calibration job is, “How often should we be doing this?” My initial response is, “The day before you have a print job that’s going to be rejected for colour!” A less glib response, however, is:

- At an absolute minimum once a year

- Preferably every 6 months

- Whenever you change ink, paper or have the press serviced

Summary

It’s worth noting that if your ink or paper does not match the standard you’re aiming for, no amount of adjustment will allow you to achieve the target standard. While it’s rare, I have encountered ink that could not get within tolerance of the target, no matter how much or how little was applied. In such cases, your choice is either to live with the discrepancy or to change your inks.

Inevitably, this has become quite a long post. While there are many more issues to discuss that can affect final colour—such as ICC profiles applied to digital artwork and the common scenario where a customer wants the print to look like something that doesn’t conform to the ISO standard—I’ll leave it here for now having covered the main points of process control necessary to achieve acceptable colour on press.

If you’d like more advice or to book a calibration visit, please contact us.

Andrew Aldridge – January 2025